New research on tungsten unlocks potential for improving fusion materials

Researchers have uncovered new insights about tungsten's ability to conduct heat, which could lead to materials advancements for fusion reactor and aerospace technologies.

In the pursuit of clean and endless energy, nuclear fusion is a promising frontier. But in fusion reactors, where scientists attempt to make energy by fusing atoms together, mimicking the sun's power generation process, things can get extremely hot. To overcome this, researchers have been diving deep into the science of heat management, focusing on a special metal called tungsten.

New research, led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, highlights tungsten's potential to significantly improve fusion reactor technology based on new findings about its ability to conduct heat. This advancement could accelerate the development of more efficient and resilient fusion reactor materials. Their results were published today in Science Advances.

SLAC scientists explain: What is inertial fusion energy?

Following ignition demonstrations at the National Ignition Facility, the prospect of developing a fusion energy source using lasers looks brighter than ever. Here, SLAC experts weigh in on what it will take to develop the science and technology toward that aim and how the lab and its partners will contribute.

"What excites us is the potential of our findings to influence the design of artificial materials for fusion and other energy applications," said collaborator Siegfried Glenzer, director of the High Energy Density Division at SLAC. “Our work demonstrates the capability to probe materials at the atomic scale, providing valuable data for further research and development."

Keeping cool under pressure

Tungsten is not just any metal. It's strong, can handle incredibly high temperatures, and doesn't get warped or weakened by heat waves as much as other metals. This makes it particularly effective at conducting heat away quickly and efficiently, which is exactly what's needed in the super-hot conditions of a fusion reactor. Rapid heat loading of tungsten and its alloys is also found in many aerospace applications, such as rocket engine nozzles, heat shields and turbine blade coatings.

Understanding how tungsten works with heat offers clues on how to make new materials for fusion reactors that are even better at keeping cool under pressure. In this new research, the scientists developed a new way to closely examine how tungsten manages heat at the atomic level.

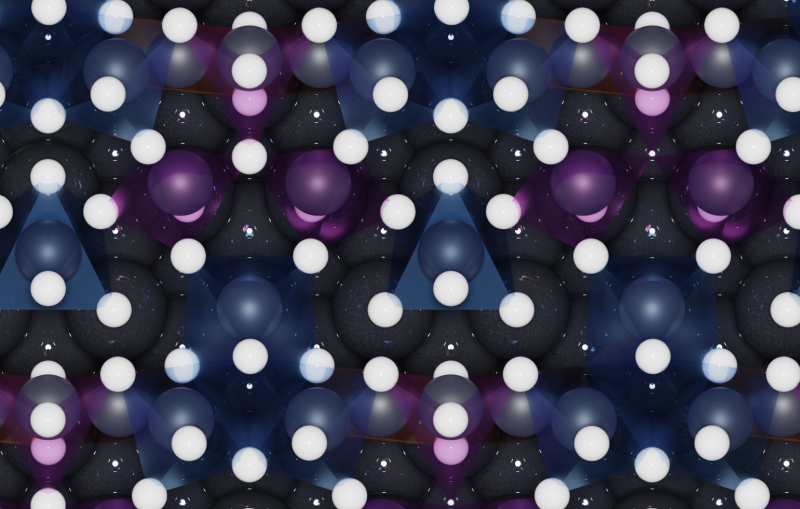

The research team set out to explore the phenomenon of phonon scattering—a process where lattice vibrations within a solid material interact, playing a critical role in the material's ability to conduct heat. Traditionally, the contribution of phonons to thermal transport in metals was underestimated, with more emphasis placed on the role of electrons. Through a combination of modeling and state-of-the-art experimental techniques, the research team shed light on the behavior of phonons in tungsten.

Untangling contributions

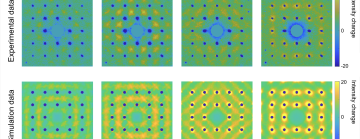

At SLAC's high-speed “electron camera” MeV-UED, the researchers probed the material with a technique called ultrafast electron diffuse scattering (UEDS), which allowed the team to observe and measure the interactions between electrons and phonons with unprecedented precision. This method involves shooting a laser to excite the electrons in tungsten and then observing how these excited electrons interact with phonons. The UEDS technique captures the scattering of electrons off phonons, allowing researchers to observe these interactions in real time with incredible precision.

UEDS allowed the researchers to distinguish between the contributions of electron-phonon and phonon-phonon scattering to thermal transport. This differentiation is key to understanding the complex workings of heat management in materials subjected to the harsh conditions of a fusion reactor.

“The challenge lies in distinguishing the contributions of phonons from electrons in thermal transport,” said SLAC scientist Mianzhen Mo, who led the research. “Our paper introduces a state-of-the-art technique that resolves these contributions, revealing how energy is distributed within the material. This technique allowed us to precisely measure the interactions between electrons and phonons in tungsten, providing us with insights that were previously out of reach.”

The study's results showed that in tungsten, the interaction between phonons themselves is much weaker than expected. This weak phonon-phonon interaction means that tungsten can conduct heat more efficiently than previously thought.

"Our findings are particularly relevant for designing new, more robust materials for fusion reactors," said collaborator Alfredo Correa, a scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL). “Such precise experiments provide excellent validation for the new simulation technique we employed in this work to describe heat tranport and the microscopic motions of atoms and electrons, allowing us to predict how materials will behave under extreme environments.”

If you can’t handle the heat…

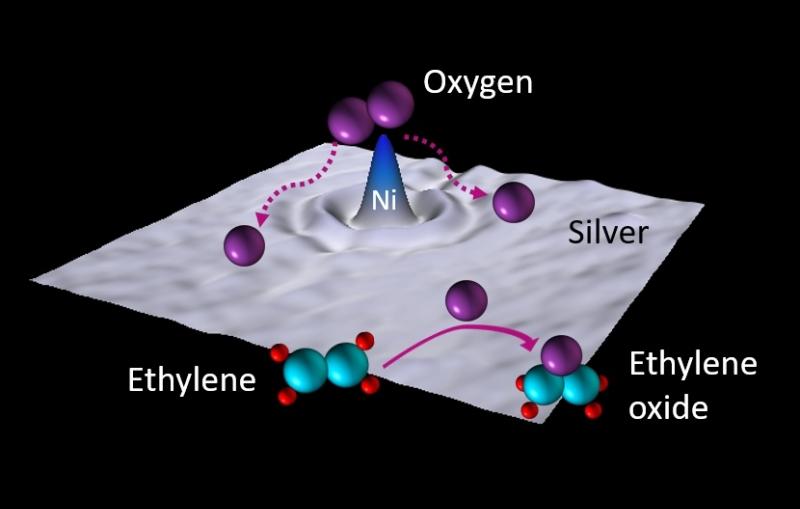

Following up on this research, the team plans to investigate the impact of impurities, such as helium, on tungsten's ability to handle heat. Helium accumulation, a product of fusion neutron-induced transmutation in materials, can affect the material's performance and longevity.

"The next phase of our research will explore how helium and other impurities impact tungsten's ability to conduct heat," Mo said. “This is crucial for improving the lifespan and efficiency of fusion reactor materials.”

Understanding these interactions is critical for validating fundamental modelling and developing materials that can withstand the rigorous demands of a fusion reactor over time. This could lead to even better materials for not just fusion reactors but also in other fields where managing heat is critical, from aerospace to the automotive industry to electronics.

"This research is not just about improving materials for fusion reactors; it's about leveraging our understanding of phonon dynamics to revolutionize how we manage heat in a wide range of applications," Glenzer said. "We're not just enhancing our understanding of how materials behave under extreme conditions; we're laying the groundwork for a future where clean, sustainable fusion energy could be a reality.”

MeV-UED is an instrument of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser facility. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was supported by the DOE Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at SLAC and the DOE Computational Materials Sciences Program at LLNL.

Citation: M. Mo et al., Science Advances, 13 March 2024 (10.1126/sciadv.adk9051)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.